12th November 2019

As a part of the “Wikimedia Commons Data Roundtripping” project facilitated by me in my role at the Swedish National Heritage Board we ran a pilot together the Swedish Performing Arts Agency around crowdsourcing translations of image descriptions this spring. In this post I’m briefly sharing some of my observations related to how AI assisted translations impacted the crowdsourcing campaign.

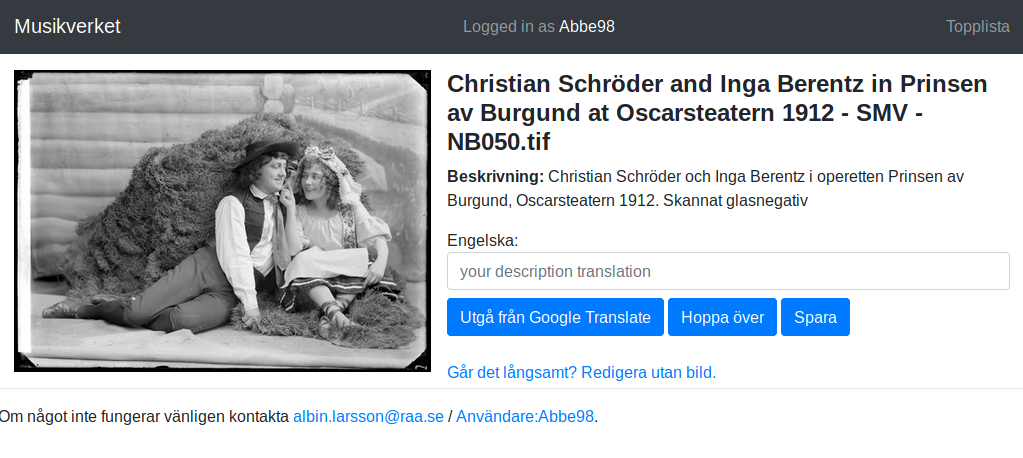

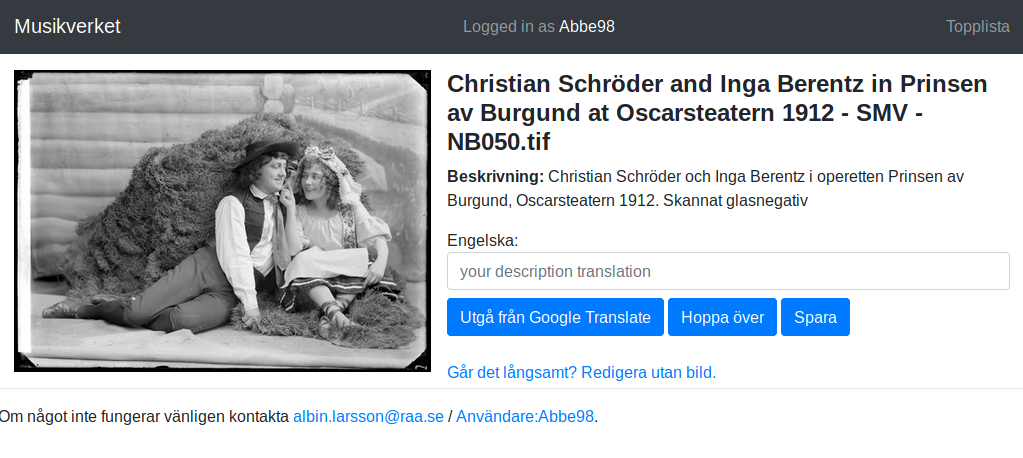

So to begin what did we do? We uploaded 1200 images to Wikimedia Commons all with descriptions in Swedish. Then we invited people to translate those descriptions into English using a tool built for that specific purpose.

In addition to the empty input field for the user to fill in there was also the “Google Translate” button. This button would prefill the input with the automatic translation from Google (the user would still need to edit/submit it). Except it was a little easier said then done…

Every now and then there would be an encoding error in the string returned from Google:

“Anna-Lisa Lindroth as Ofelia in the play Hamlet, Knut Lindroth\'s companion 1906. Scanned glass negative”

This type of errors were discovered during development of the tool but we decided to leave the issue there to see if users would catch it.

A while into the crowdsourcing campaign it became clear that the descriptions translated by Google Translate were of higher quality then the ones done entirely by humans. While it didn’t manage all the theater specific terms it was still simply more consistent.

After an user had been using the Google Translate button for a while without many or any edits needed they no longer caught obvious error such as the example above. The pilot wasn’t large enough to prove anything statistically it indicates that users quickly starts trusting automated data if an initial subset of it is of high quality.

If you want to know more about the entire project that was much larger then this pilot there is plenty for you to read.

30th October 2019

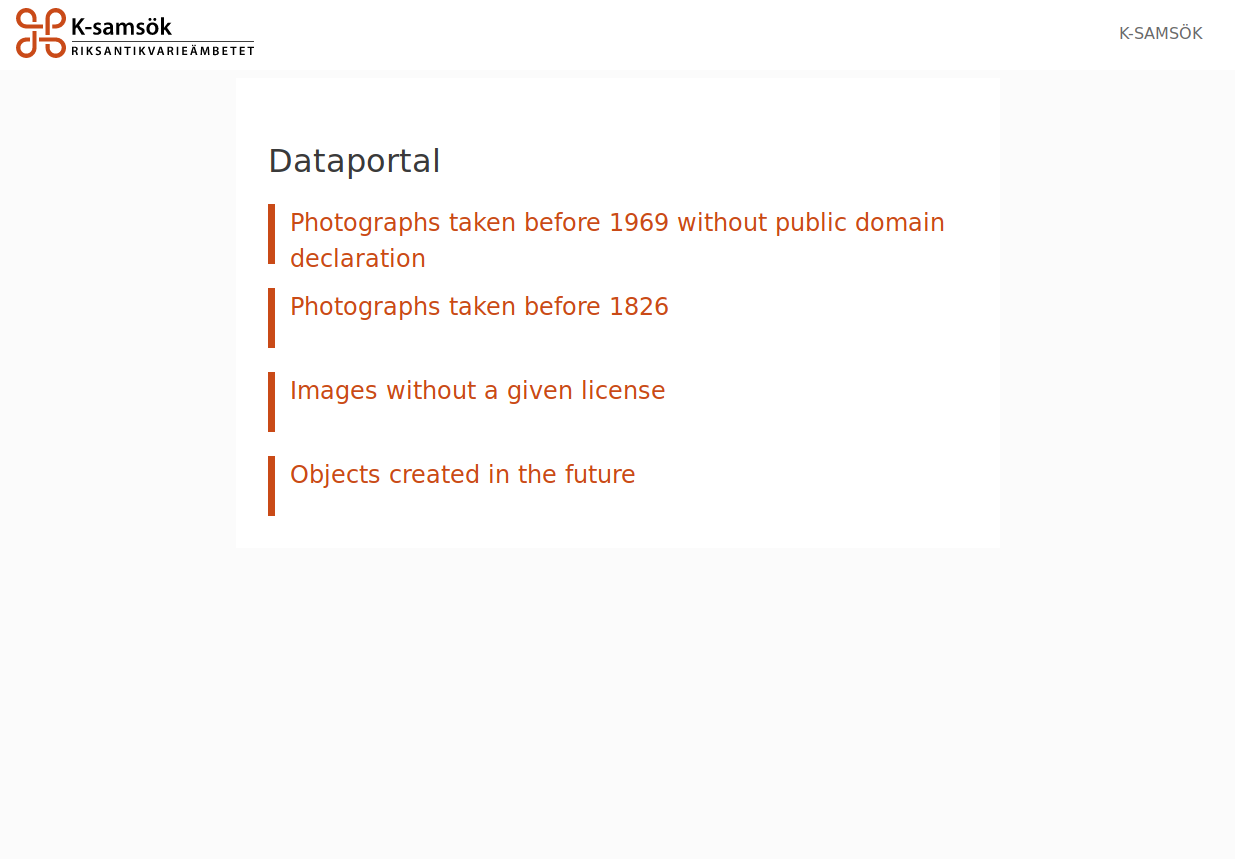

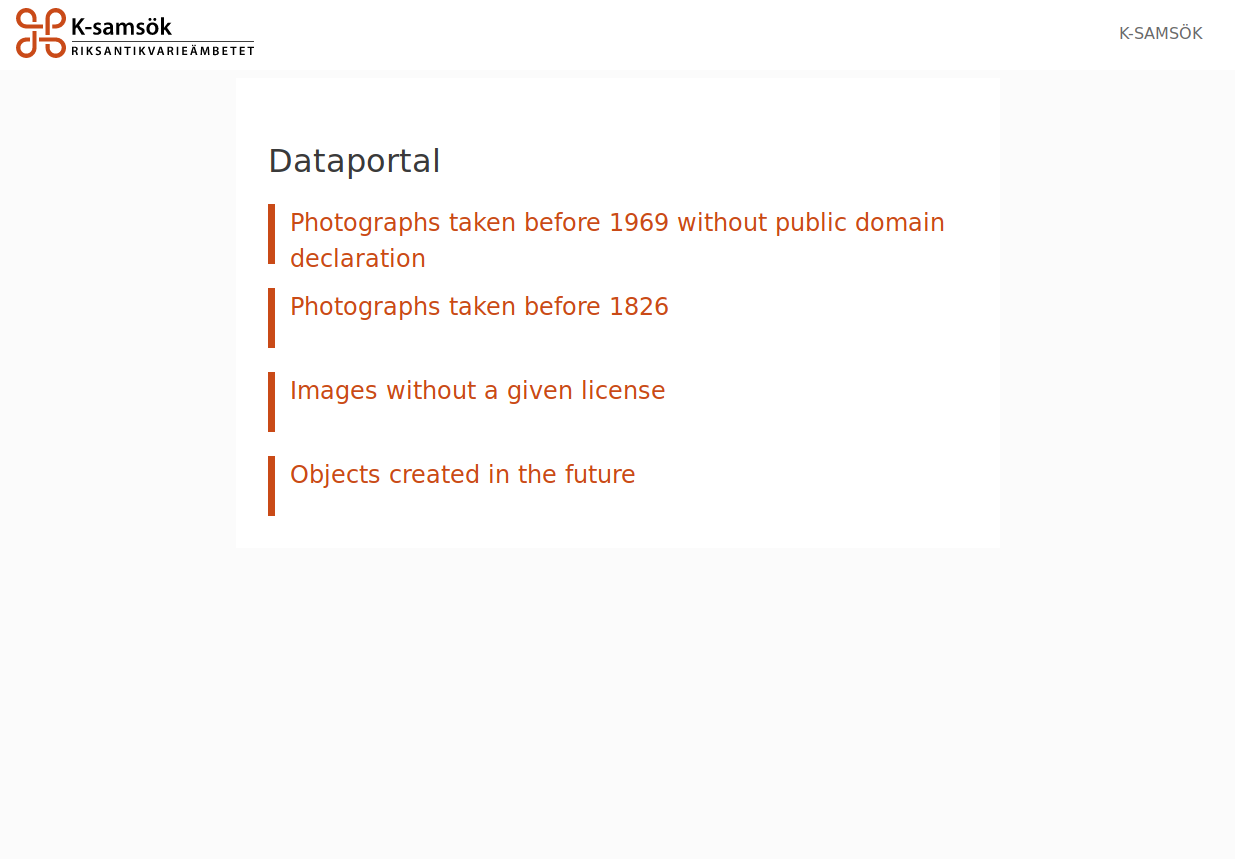

In this post I’m introducing a new data quality portal that we are currently testing with the K-samsöks data partners. It’s a data quality tool without any percentages or metrics.

To solve data quality issues at cultural heritage institutions (or anywhere) two key things need to be achieved:

- Awareness - individuals need to be aware of the specific data quality issues present in their data.

- Actionability - individuals need to have the tooling and knowledge to find individual and fix quality issues.

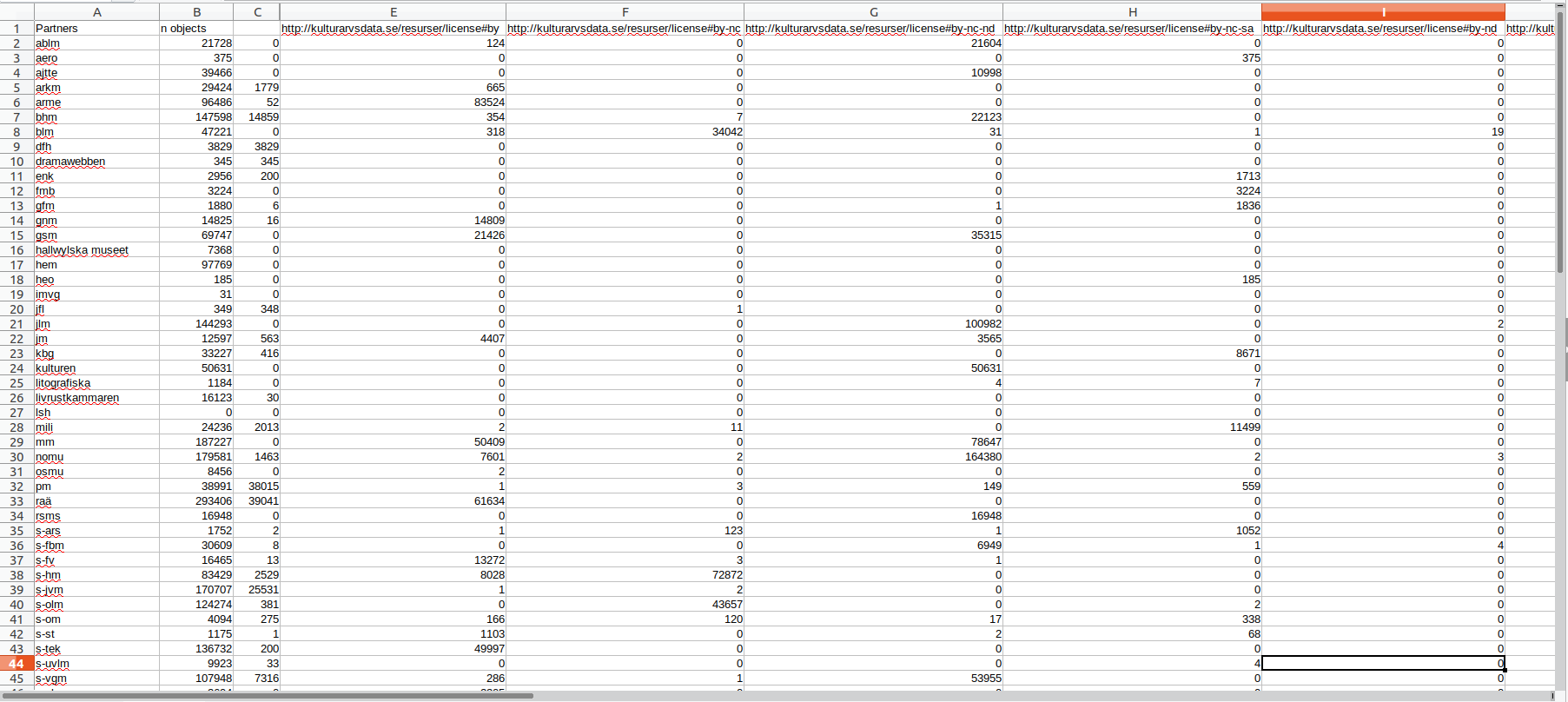

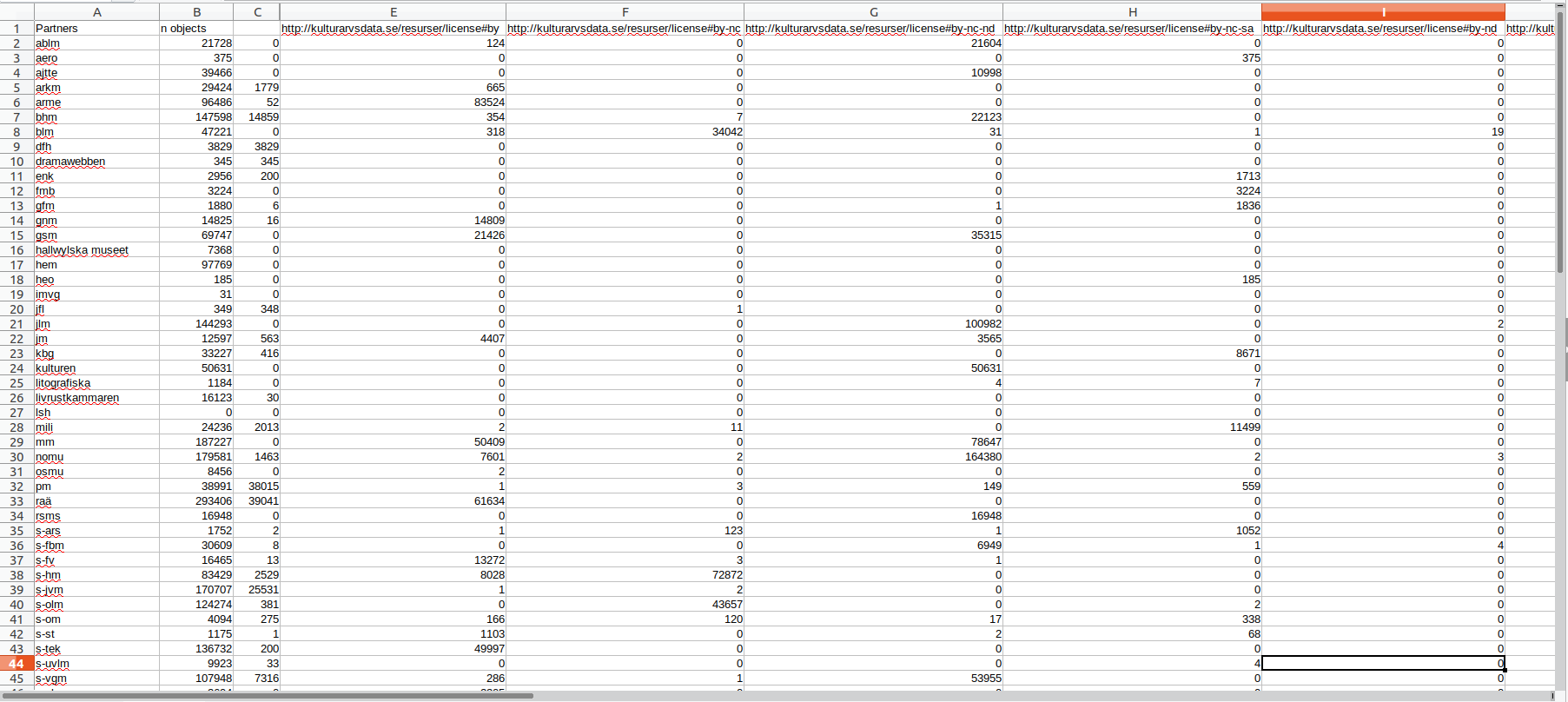

The first one is something that aggregation actors have been targeting for a while through spreadsheets and percentages. The screenshot below shows the second(ish) iteration of our licensing statistics/issues spreadsheet that we share with data partners (the code behind it is written by my colleague Marcus and it’s open source).

Some institutions have been able to act upon the insights given by this, while others have not. A common issue is the lack of being able to query their own data, often this is because of lacking capabilities of collection management systems, sometimes it’s a combination of this and user knowledge. No matter what it’s a barrier.

Being an aggregator allows us to lower barriers for 70+ data partners so by curating and building a GUI around advanced queries. So instead of not being able to query their data or being stuck in writing some boolean and/or whatever query in their CMS they can now list problematic objects within a few clicks.

The current data quality queries available to data partners in the current proof of concept version of the data portal (we and partners have plenty of other ones in mind).

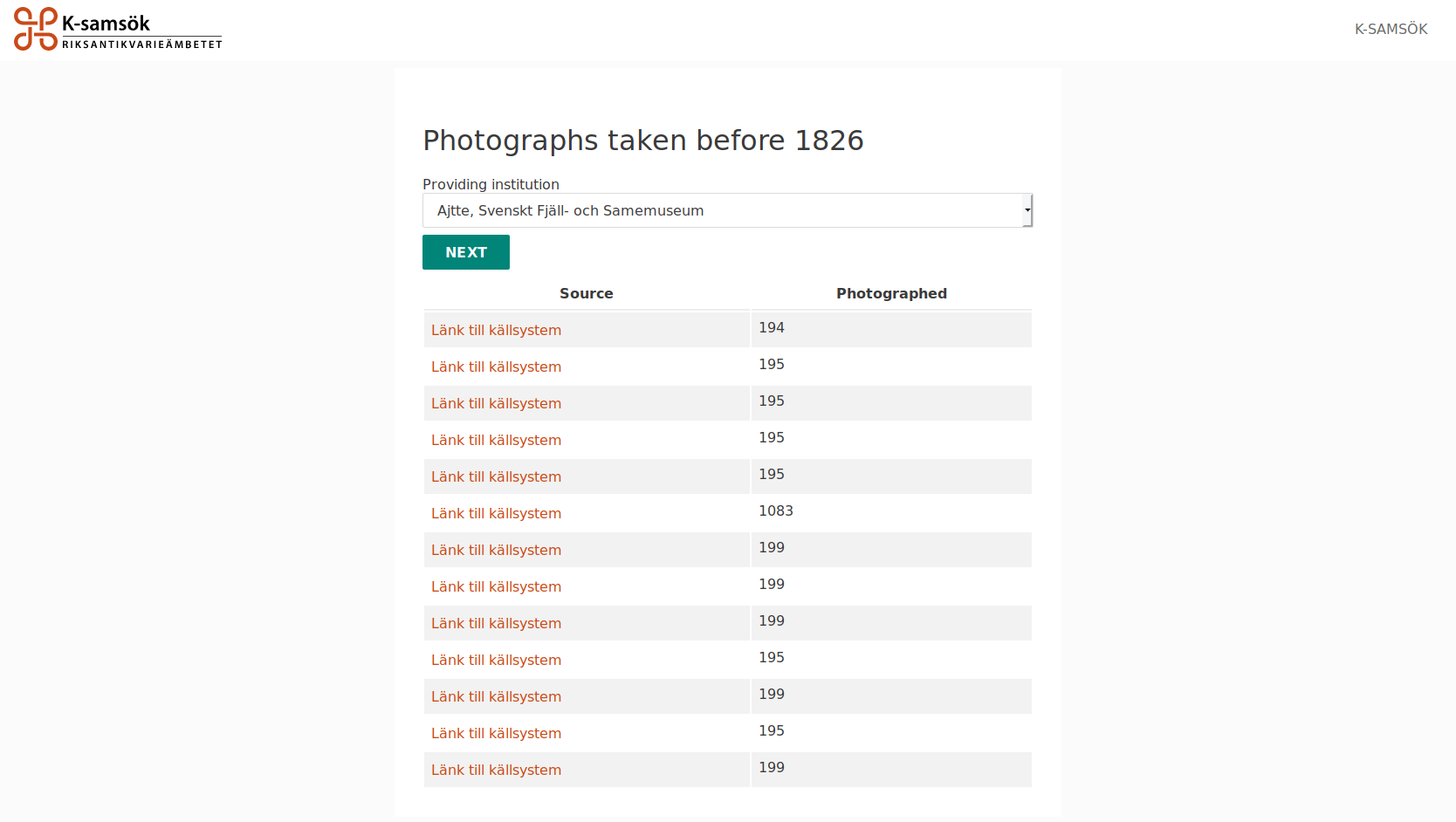

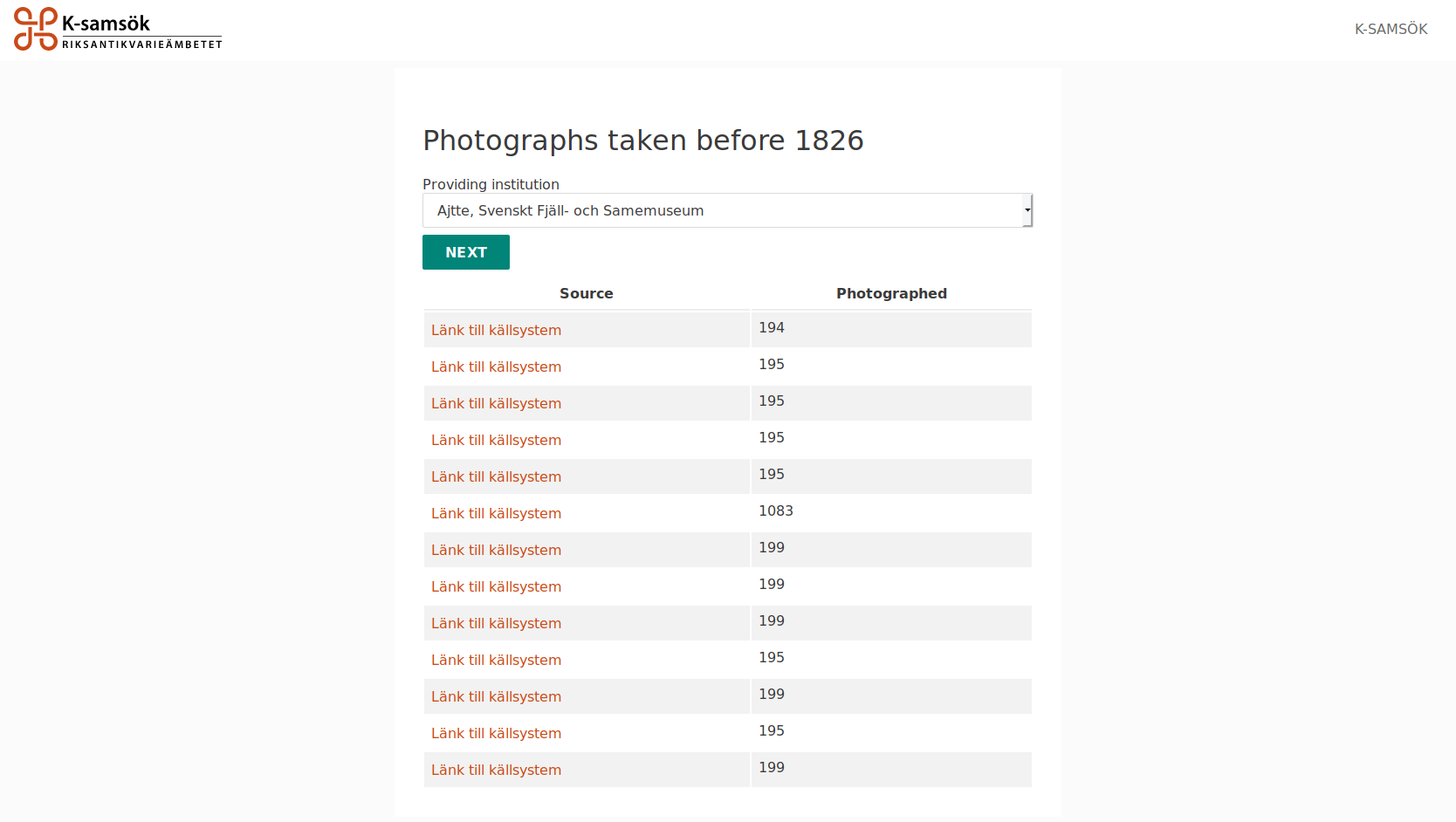

Following the selection of quality query and providing institution a list of problematic or possible problematic objects are presented to the user in a list containing a link back to the source page or CMS as well as other metadata that might be relevant for the given query.

In a couple of weeks it will be clear if this new approach have an impact. I know what I’m betting on.

4th July 2019

I have for the last few yeas had a online privacy approach in the style of “Do not put all eggs in the same basket” or exemplified in the style of “If I use Google for email I won’t use it for browsing the web”.

Now after a few years of empirical learning I have decided to change this approach. It’s clear that the owner of “my” online data (the irony) is seldom static nor does it keep the data within its own walls.

My new approach is to create as little online data as possible. Below are some actual examples of things that has lead me towards this decision.

- Recruiting firms aggregating online data about me. Although I’m not a software developer by profession I get a lot of spam from recruiting firms. I have found that these firms often has aggregated public information about me from sources such as Github and Twitter.

- Recently I discovered that two sites my employer (a government agency) hosts had been relaying on a third party service that fingerprinted our users for years and sold the data.

- Opera going from being a Oslo based company to being bought a random Chinese company. As an user I was never informed that “my” data changed owner.

There are probably plenty of cases were these types of issues have been combined and exposed information about me to third parties unknown to me.

What I’m doing to limit online data about me

- Switching from Opera to Firefox while applying extensions such as uBlock Origin. Although Firefox do not have all the nice features that Opera has (tab preview, popup video and a built in RSS reader) it should be a quite effortless switch.

- I will be creating a online presence inventory. A list of sites that I know have some non-anonymous data about me such as a user account because the first step towards action is awareness. This first step is not much of an effort but once I start to delete accounts and other information it will likely take up plenty of time.

- I will host my own DNS server and apply a whitelist. I will block every single domain that I have not looked into myself. This will break the web for me and take quite some effort to get right but it will be worth it.

- I will intercept common CDN services with one hosted on my own network. This should be a rather easy task and I’m sure there are some good solutions out there already in use.

One might see me as paranoid or a privacy geek but these actions comes from actual concerns and real world examples.